One of the downsides of getting older – I am now 62 – is that one’s friends die. Friday, it was the turn of Patrick Leigh Fermor, aged ninety-six, and I am having trouble accepting that he is gone.

One of the downsides of getting older – I am now 62 – is that one’s friends die. Friday, it was the turn of Patrick Leigh Fermor, aged ninety-six, and I am having trouble accepting that he is gone.

By Paul A. Rahe

First published in Ricochet on 12 June 2011.

I first met Paddy in the summer of 1983. I was working then – oddly enough, as I am working right now – on a book on classical Sparta, and I had a grant and a hunch. The Spartan way of life was based on something like slave labor. The Spartans ruled the southernmost two-fifths of the Peloponnesus and drew their livelihood from farms worked by their helots (the word in Greek means captives), who reportedly outnumbered them seven-to-one. In their realm, there were and are two river valleys – one in Laconia and the other in Messenia – divided by a mountain range named Taygetus, and there was and is mountainous terrain elsewhere in Messenia. I had read extensively about the history of slavery, and I was persuaded that there must have been gangs of runaway helots in the hills of Messenia, as there later were in early modern Jamaica and in other locales where servile labor was the norm and there was wilderness nearby. I knew that the Greek resistance during the Second World War had operated in the mountainous country of northern Greece, but I knew little about their operations in the Peloponnesus. A fellow ancient historian who had lived in Greece for some years and had tried to make it as a novelist said to me, when he heard of my hunch, “You ought to talk to Paddy Leigh Fermor. He lives down there, and he fought with the resistance on Crete. He lives in Kardamyle. You should look him up.”

And that is precisely what I did. With the grant I had been given, I bought a plane ticket, and I spent some weeks in the company of a former student who hailed from Thessalonica, exploring the Peloponnesus – by boat, in a rental car, and on foot. Kardamyle was in the Mani – the southernmost prong of the Taygetus range, and it was one of the towns that Agamemnon had offered Achilles in an attempt to get him to take the girl back. When we got there, however, Paddy was away. So I mailed him a brief note and moved on. When we returned, I telephoned him – and he immediately invited the two of us to lunch.

Leyla, who had long been their cook, produced a sumptuous feast. We ate, and we drank, and then we drank some more – and the next thing we knew it was 5 p.m. Paddy and Joan, fearful that we were too intoxicated to successfully traverse the half-mile on foot back to Kardamyle, offered us beds. It was one of the most delightful afternoons that I have ever spent. The historian and journalist Max Hasting has observed that Paddy was “perhaps the most brilliant conversationalist of his time.” Never have I encountered anyone as entertaining.

Paddy was – there is no other word for it – a hero. He lived the strenuous life. There was in him an exuberance that could not be contained. Christopher Marlowe, who was of a similar temperament, managed to make it through the King’s School in Canterbury, but Paddy did not. There was some hanky-panky with the daughter of a greengrocer, but that cannot have been the whole story. “He is a dangerous mixture of sophistication and recklessness,” his housemaster wrote in an official report, “which makes one anxious about his influence on other boys.” I would have been anxious myself.

Not long thereafter, with the support of his mother, who mailed him a fiver from time to time, Paddy set out in December, 1933 by ship for the Hook of Holland – and walked from there to Constantinople and on to Mount Athos and its monasteries. It took him more a year, and you can read about his adventures in two of the books that he later published – A Time of Gifts (1978) and Between the Woods and the Water (1986) – which together constitute what the Germans call a Bildungsroman. In those volumes, you will encounter a world of peasants and aristocrats, of socialists and fascists that no longer exists.

On that journey, Paddy met an older woman. He was nineteen. She was married and thirty-one. You can find a description of the beginning their affair in the second of the two volumes mentioned above. Her name was Bălaşa Cantacuzino, and she was a Romanian princess descended from the Byzantine royal house. When his trip was over, they settled down together, oscillating between Athens and at her country house in Moldavia. Then came the Second World War, and he volunteered for the British army. The two would not meet again until after the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1989.

During the war, Paddy fought in Albania, Greece, and on Crete. After being evacuated to Cairo, he joined the Special Operations Executive and spent much of the remainder of the war running guerrilla operations in the mountains of Crete. He left the island in May, 1944 under truly exceptional circumstances. On 26 April 1944, on a bet made with friends back in Cairo, Paddy, W. Stanley Moss, and a group of Cretan shepherds kidnapped General Karl Heinrich Georg Ferdinand Kreipe, the German commander on the island.

The two Englishmen dressed up as German police corporals and stopped Kreipe’s car as he was making his way back one evening to his villa near Knossos. Having eliminated the chauffeur, Paddy put on the general’s hat, and Billy Moss drove the car. Kreipe was hidden beneath the back seat – on which three hefty Cretan andartes sat. They then bluffed their way through Heraklion and an addition twenty-two checkpoints before ditching the car and hiking into the mountains – where, for three weeks, they evaded German search parties before being picked up by a British motor launch on the south coast.

At one point, as they neared the top of Mount Ida at the break of dawn, Kreipe quoted the first line of Horace’s ode Ad Thaliarchum – “Vides ut alta stet nive candidum Soracte” (See how Soracte stands white with snow on high), and Paddy finished the poem to its end. “At least,” the general remarked, “I am in the hands of gentlemen.” In the days that followed, before they were evacuated to Cairo, the two discussed Greek tragedy and Latin poetry. In 1972, they would meet again in Athens to tape a television show. Afterwards, Paddy once told me, they went out to dinner and sang old German drinking songs. Well before that time, however, Billy Moss had published a book on the incident entitled Ill Met by Moonlight, and Michael Powell had made a movie with the same name in which Dirke Bogarde was cast as Paddy.

Before the war, Paddy had begun his literary career with a translation of of CP Rodocanachi’s novel Forever Ulysses (1938). Afterwards, he began to write books of his own. The first of these was a travel book, focused on the West Indies and entitled The Traveller’s Tree (1950). It won the Heinemann Foundation Prize for Literature. Soon thereafter he published a novel set in Martinique entitled The Violins of Saint-Jacques (1953), which was turned into an opera by Malcolm Williamson; a meditation on monasticism entitled A Time to Keep Silence (1957); and two travel books focused on two of the wilder regions of Greece: Mani (1958) and Roumeli (1966). That all of these remain in print is no surprise. Five years ago, Paddy was described to me by an Oxford don as the greatest living master of English prose.

In 1984, I was offered by the Institute of Current World Affairs a fellowship two years in length, which would take me to Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus, and I jumped at the chance to situate myself in Istanbul (where I lived in the neighborhood in which Claire Berlinski now resides) and to explore the landscape and experience the seasons in the world within which the ancient Greeks had made their home. I spent most of my time in Turkey, exploring its nooks and crannies and writing long newsletters about contemporary affairs. From time to time, however, I hopped a plane to Greece, interviewed various figures in Athens, and partied with some journalists I knew (Robert Kaplan was based in Athens in those days).

On those occasions, I always took a bus to Kardamyle and spent a few days with Paddy and Joan. Their house, which Paddy had designed himself, was built out of stone and situated on a bluff overlooking the sea. We rose when we chose, ate breakfast separately, and Paddy put pen to paper while Joan saw to the management of the establishment – and I read a novel, a travel book, or something pertinent to the composition of my first book Republics Ancient and Modern (which Paddy would later review for the Christmas books section of The Spectator).

After lunch, where we drank a considerable amount of wine, we would nap. Then, we would go back to work, and, at about 5 p.m., Paddy and I would head off for an extended walk in the mountains. He was about seventy at the time, but he was astonishingly vigorous. Every day he would go for a long swim, disappearing into the drink and reappearing a half hour later. On his seventieth birthday, he swam the Hellespont – something that very few men half that age could manage. (I know. I watched from a motor launch once while a thirty-something friend gave it a try).

Before dinner, there were drinks. “C’est le moment,” Paddy would say, quoting Victor Hugo, “quand les lions vont boire.” Dinner itself was a feast, and it often ended with the singing of songs. Paddy taught me The Foggy, Foggy Dew, and I taught him They Call the Wind Maria. After a week or so, I would take the bus back to Athens and head on to Greek Cyprus or back to Istanbul. On one such occasion, I carried to the British embassy the manuscript of Between the Woods and the Water. From there, I gather, it was sent on by diplomatic pouch to Paddy’s publisher in London. He had served his country well, and his compatriots took good care of him. He was offered a knighthood in 1991 and finally accepted one in 2004.

In the 1990s, when I came to Greece in the summer, I would fly in to the Athens international airport, and then I would generally take a bus across to the domestic airport, go up to the counter, look over the available flights, and book a ticket for an island that I had never visited. Then, after a week or so on, say, Paros, I would go down to the harbor and catch whatever boat there happened to be – for Lemnos or Andros or some other unfamiliar spot. Eventually, after having spent three or four weeks exploring, I would return to Athens and go down to the Mani to see Paddy and Joan. The routine in Kardamyle was the same – except that, towards the end of the millennium, Paddy was less able to hike in the mountains.

After I got married, there was less traveling. In 2003, however, I did manage to see Paddy in England at their country house in Gloucestershire (Joan was the daughter of a Viscount). Ours was a subdued lunch. Joan had died at the age of ninety-one in Kardamyle hardly more than a week before. I last saw him in Kardamyle in March, 2006. I had spent Michaelmas and Hilary Terms as a Visiting Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford, and I was about to take up a similar fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin. There were, however, two weeks in which we had no place to call our own. So my wife, our daughters, and I flew to Greece, rented a car, and, after a brief visit to Athens, headed to Delphi and on from there to the Peloponnesus – where we stopped at Olympia, the Apollo Temple at Vassae, Mycenae, and other sights. I tried to call Paddy, but the Greeks had added a digit to the old number, and I could not figure it out. So we drove to Kardamyle and then out to his house on the outskirts of town, and I rang the bell.

And there he was – older, quite a bit slower in his gait, but very much himself. “Paul Rahe,” he said. “I don’t believe my eyes. Come in, my dear boy.” And when I mentioned my family, his response was immediate: “Bring them in. You can all stay here.” And so we did. That night we took him to dinner at the restaurant in town that Leyla now runs, and we sat up late talking and drinking. His eyesight was not good. He had glaucoma and in the candlelight at one point was not sure that we were still there. He had had a heart attack and had a pacemaker. He could hardly walk up the drive to the highway. But there was still a twinkle in his eye, and he was as alive as ever.

He was also writing, and in his nineties, after decades of resistance, he had actually learned how to type (no one could read his handwriting). A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water were intended to be the first two parts of a trilogy. With the third part, he had had a terrible time. After 1989, he had returned to Roumania and Bulgaria to retrace his steps, and it was not as he remembered it. When I visited in the 1990s, I would ask about the third volume, and Joan would pull me aside and tell me not to mention it. “He is having trouble with it. He is very frustrated. That trip back to review his path robbed him of the confidence he had in his memory,” she once said.

When I saw Paddy in 2006, however, he was halfway done with the manuscript, and he was going over it to look for things that could be cut. I gather that somewhere in the house at Kardamyle there is a manuscript and that on the cover it reads “Volume Three.” I wonder what he called it. That last night just over five years ago, he, my wife, and I tried to come up with a title, and we could not think of anything satisfactory.

If and when the third volume of his trilogy does come out, I will buy a copy. Reading it will, I am confident, bring back the man. His other books do. I doubt, however, whether I will ever meet the like again – and that I very much regret. Perhaps the biography that Artemis Cooper is writing will relieve my gloom.

Have a suggestion,for a title.Between the Horizon and the Dockyard,

Andrew – are you in some way related to John Pendlebury?

Of course, count me in!

Tom, I don’t really understand what you mean with your last sentence, is Artemis participating in our discussions here?

By the way, in a Greek obituary published the day before yesterday in To Vima and based on an interview with Paddy several years ago, I read that Paddy and Antonis Benakis were friends and that Benakis allowed Paddy to use his office for writing, after closing time of the museum he founded.

Erik – she is not ‘here’ but I hope to meet her quite soon to discuss a range of issues including a PLF Society etc. In 2015 we will have “PLF 100” – something to prepare for don’t you think? You are the sort of guy who I am sure could contribute 🙂

Many thanks to Paul Rahe for sharing his memories of Paddy Leigh Fermor, and appreciation to Tom for republishing the piece here. These remembrances live.

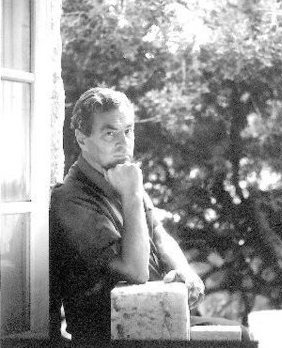

The photo of Paddy at home is wonderful. I hope that someone will take special care of Paddy’s library, notebooks, manuscripts, letters, &c. A great deal will be lost forever if those are scattered or separated. What were Paddy’s wishes about those items? Please post a note here or to my email at Durrell 2012 if you have information. I would be willing to help in any way that I can.

Charles – as I understand it, his house in the Mani has been left to the Benaki museum. One would guess, that it would include many of his possesions. The expectation being that it would be possible to visit at some point. However, maybe some of his books/papers may be subject to further arrangements?

One more thing to discuss with Artemis at some point in the next few weeks.

Thanks for that follow-up, Tom.

That is good news that the house and contents might be kept intact. I think that it is crucial to keep those working materials in one place if possible. On the most immediate level, of course, the reading library, reference books, notebooks, diaries, mss &c. are PLF’s imprint — preserving the patterns of his attention when looked at in situ at the house. (Preservation of the materials against the climate &c. may be another issue.)

For a contrasting example of what can happen, see the case of the Lawrence Durrell materials. Those notebooks, typescripts, and books are held in several good or even great libraries — including the BL — but having a diaspora that scatters different lots into public and private holdings on several continents is a real stumbling block for anyone wishing to piece this fragment to that fragment.

Paul – I was at the start of “Between the Woods and the Water” – at the bit where he had stumbled on an encampment of Romanian gypsies, on a borrowed horse, at night – and exchanged words from their Hindi origin tongue – especially the word ‘pani’ (which brought back my own Hindi origins) – and, as always, shared his food and bottle.. He had the rare gift of making friends at every level.

I loved your piece on him. I am especially moved by his very un-Englishness – the hospitality of the East..

I will only hope that someone will take up the publishing of his ‘3rd Volume’ – perhaps you can influence this? I need to know his route from the Iron Gates – I am planning to follow this in my little Smart car in the autumn of of 2012 – when I will leave the Smart (‘Afrodite’) at my bolthole in Pafos in Cyprus. I am now 67 and will spend my remaining years in Pafos (and Normandy), writing..

Vol 3 will come – a draft exists – I guess it will need editing. As far as I know he went south from the Iron Gates and into Bulgaria, then back up north into Romania (Wallachia) then south back into Bulgaria along the Black Sea coast to Constantinople